| Author: | Ralf Südhoff |

| Date: | 31. January 2025 |

Pop quiz: Who made this comment on the planned 2025 reduction of German humanitarian aid by half?

“Despite the cuts, Germany remains a top donor in international comparison and the criticism is therefore misguided”.

Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock?

Ex-Finance Minister Christian Lindner?

Chancellor Olaf Scholz?

In fact, the head of a German aid organisation—who I highly respect—shared this assessment a few days ago during a conversation about the Bundestag elections. Shortly afterwards, an NGO colleague echoed this sentiment, saying: “to be honest, Germany had recently been disproportionately involved and was now understandably scaling back.”

These comments reminded me of three things: first, how effective narratives can be, even among experts; second, how important it is to verify them with facts; and finally, the ongoing lack of an informed debate on what level of financial commitment is appropriate for a donor country like Germany—and by what criteria it should be measured.

So, what are the facts?

And what are the criteria for appropriate funding?

First, some good news: the Bundestag elections are less than a month away, and rarely have foreign policy issues played such a relevant role in the election campaign as they do now—particularly regarding assistance for Ukraine, the Middle East and future relations with the U.S. under President Trump.

The bad news? These topics are once again being discussed as if they were separate from questions about international cooperation, development policy and humanitarian action. And despite drastic cutbacks in these areas, the discussion—when it happens at all—remains fixated on a familiar question: should the BMZ and the Federal Foreign Office be merged?

International cooperation has always had a difficult time attracting the attention of the wider public. However, this hasn’t diminished the broad support for its work, goals or funding. For example, in 2022, 68% of respondents supported maintaining or increasing Germany’s financial commitment to development cooperation. But that support has steadily declined: by 2024, only 47% of respondents gave the same response. This shift is also evident in parliament, where not only right-wing populists but increasingly the political mainstream consider radical cuts in aid unproblematic. In the federal government, the traffic light coalition government has undone a decade of progress with its drastic cuts, particularly in humanitarian assistance, which is down 60 % since the coalition took office.). In short, German humanitarian action is at a turning point.

Much-discussed phenomena, such as right-wing populist discourse, fragmented public spheres in the age of social media, the increasing politicisation of humanitarian aid, and the geopoliticisation of international relations, certainly play a role. But there is also a key narrative at play, one that has been promulgated in almost every panel discussion during better times: the myth of a German government that foots the humanitarian bill for the entire world. This narrative is widely believed by many advocates and practitioners of humanitarian aid, and it fuels the trends described above.

To illustrate this point, it is not necessary to dive into the contentious debate over narratives that promote support for humanitarian aid based on vested interests, like migration or security policy goals, and all the advantages and disadvantages of such an approach. A simple look at the bare figures will suffice to show how the rise and fall of German humanitarian aid compares internationally.

For those currently overseeing the drastic downgrading in both finances and status, the matter is clear. For example, Christian Lindner’s letter to the Chancellor’s Office on the draft budget of 15 July 2024 states that Germany “will probably remain in second place among donor nations in 2025, despite the existing need for consolidation”. Even the Federal Foreign Office adopted this interpretation when defending the budget cuts at the launch of Germany’s new humanitarian strategy last autumn: the cuts were regrettable, but ultimately a normalisation compared to pre-Corona times, when Germany was disproportionately involved – and there was always the option to raise additional funds in the current budget year. Fighting for higher budgets sounds different (as seen in the case of the very active BMZ, whose budget was “only” cut by about 8%).

But what’s behind the narrative of a Germany that’s been footing the bill for everyone and now needs to focus on itself, with others taking their turn?

What’s correct is this: Germany has seen a steep rise as a humanitarian donor over the past ten years. In absolute terms, it has consistently been the world’s second- or third-largest donor in recent years, while some countries, particularly in Eastern Europe or the Arab world, have taken a more reserved approach. At the same time, Germany has also been the world’s third, or fourth-largest economy for many decades, which highlights how misguided it is to measure its engagement purely in absolute figures. How absurd would the German government find it if Trump were to issue a new decree cutting US humanitarian aid by over 90% to $1 billion, justifying it by saying that Germany isn’t contributing more either?

Regardless of one’s opinion on the debate over appropriate defence spending by Germany or NATO member states, there is a reason the discussion focuses not on absolute figures but on whether 1%, 2%, or even 3.5% of GDP would be appropriate. If this same metric were applied to the aid sector, avoiding direct comparisons between Germany’s budget and those of countries like Luxembourg, Germany’s standing would look entirely different, especially from a historical perspective.

Until the early 2010s, Germany was, in an almost grotesque way, a humanitarian dwarf, effectively hiding behind minimal contributions of around 100–200 million euros. However, Chancellor Merkel’s realisation in the wake of the 2015 Syrian refugee migration—that the strategic importance of humanitarian aid had been massively underestimated—led to an impressively sustained and highly respectable rise, culminating in a record budget of €3.2 billion in 2022.

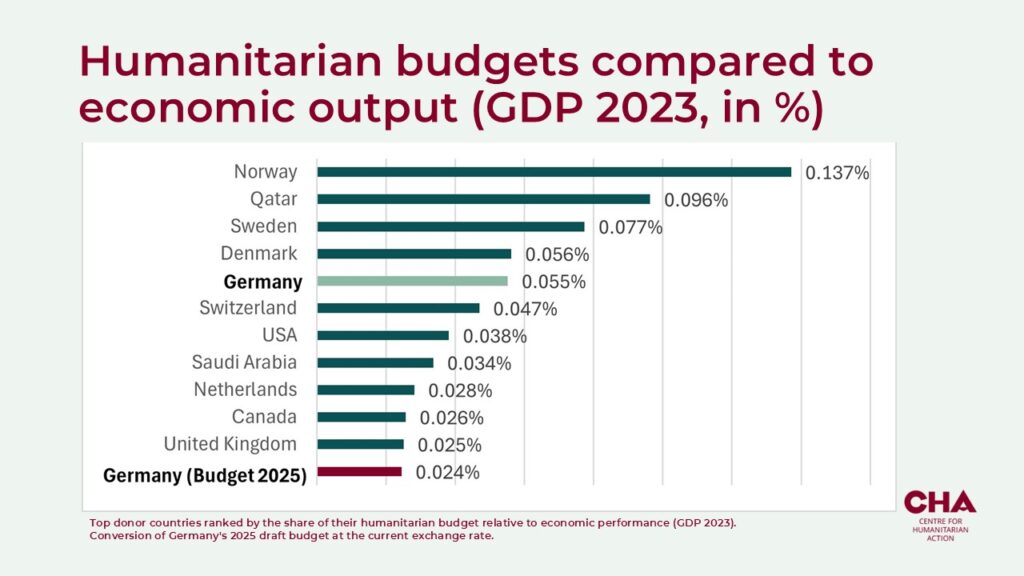

At the same time, even with this rise, Germany still doesn’t play an outstandingly leading role in humanitarian aid today. This is evidenced by CHA analyses: Even if one considers 2022 as an exceptional year due to the pandemic and instead focus on 2023—when Germany reached its second-highest humanitarian budget ever at €2.7 billion—Graphic 1 clearly shows that, even in this record year, Germany was only the world’s fifth-largest donor in relation to its economic strength. In fact, even the often-criticised Qatar contributed significantly more.

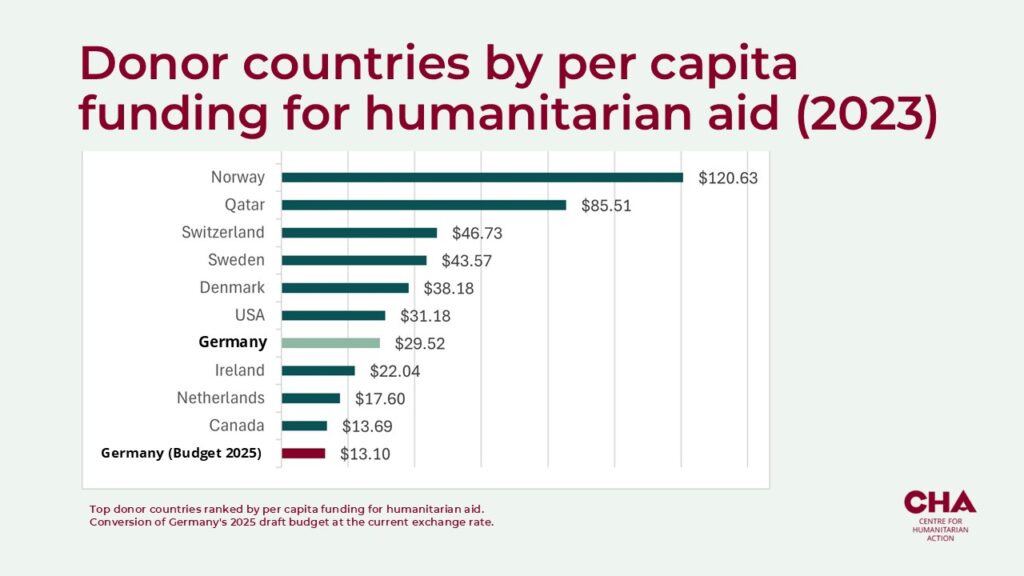

A per capita analysis presents an even more mixed picture: In 2023, Germany ranked only seventh in international comparison, with Qatar providing nearly three times as much aid per capita—around $87 per person, compared to Germany’s less than $30 (see Graphic 2).

The figures become even more striking when comparing Germany’s planned humanitarian budget for 2025 (€1.04 billion) with the most recent contributions from other donors in 2023. Per capita, Germany would provide less than $13 per person per year in humanitarian aid, equating to just about $1 per person per month. Despite economic challenges, other countries have managed to contribute significantly more, including Denmark (three times as much), Switzerland (four times as much), Qatar (seven times as much), and Norway (ten times as much).

When measured against economic performance, Germany’s position in 2025 would decline even more sharply, falling out of the world’s top 10 donors altogether. With just 0.024% of GDP allocated to humanitarian aid, countries like Saudi Arabia would contribute over 40% more, Qatar four times as much, and Norway nearly six times as much.

These assessments make one thing clear: Over the past ten years, Germany has made impressive efforts to assume an appropriate role as a humanitarian donor. However, in reality, this has been more of a normalisation of its engagement than an outstanding or excessive leadership role as a global payer. Without a doubt, countries in Eastern Europe and, in the medium term, emerging BRICS states such as China and India might look to Germany’s development as an example in the future. However, they are unlikely to do so if Berlin now executes a drastic U-turn, relying on the ever-convenient argument that it is time to focus on its own economic difficulties. First, almost every country in the world could use this argument right now. Second, the argument itself is inherently flawed and illogical.

The measure of GDP share for appropriate contributions is specifically designed to account for a donor’s economic development, which is why expectations for Germany have already been adjusted in light of its stagnating or declining economy. Moreover, even within the national budget, there is a strong case for increasing humanitarian aid. This is true even under the current draft budget, as no ministry has been required to make such disproportionate cuts as the Federal Foreign Office. Even within the Foreign Office’s reduced budget, a significantly smaller share is now allocated to humanitarian aid compared to the past, without any compelling necessity.

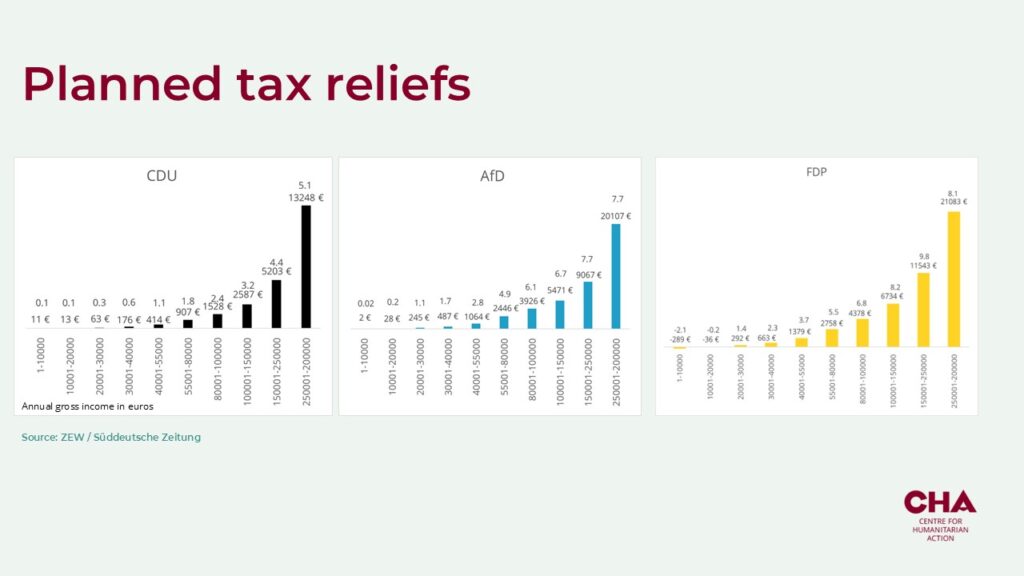

This becomes even clearer when considering a future German government and the fiscal policy proposals of some of its potential key figures. The very parties that argue most fiercely that Germany must cut spending and drastically reduce aid for the world’s poorest are simultaneously planning massive tax breaks, particularly for the wealthiest in the country. Thanks to calculations by the ZEW, these tax cuts for Germany’s top earners can now be quantified in hard euros (see Graphic 3).

While Germany, as described, will soon be able to allocate just $1 per citizen per month for life-saving emergency aid, largely due to pressure from the FDP, the Liberals are simultaneously planning significant tax cuts for high-income households. Those earning over €150,000 per year would see nearly €1,000 in monthly tax relief, while those earning a quarter of a million euros or more would be allowed to keep an additional €1,800 per month. Similar redistribution plans are being pursued by the self-proclaimed “party of the common people,” the AfD, and, in a slightly softened form, by the CDU/CSU—while low-income earners would see little to no relief. And yet, we are supposedly less and less able to provide aid for millions of Sudanese facing starvation, for freezing babies in Gaza, or even to maintain any support at all for Latin America, as Germany plans to withdraw its assistance entirely in light of its halved budget. These are the priorities of a so-called community of values in Germany and Europe.

But what criteria should be used to set the right priorities?

Beyond moral appeals, it is striking how underdeveloped the debate remains on what constitutes an objectively appropriate level of humanitarian aid per donor state and economy. So far, two main approaches have emerged:

One approach, known as the “Fair Share” model, such as those recently developed by Oxfam, has attempted to calculate appropriate funding levels for specific crises and international appeals. For instance, it determines what a fair contribution to Syrian aid would be for each OECD/DAC country based on its economic strength. These models distribute humanitarian needs across all major economies, including BRICS and Arab states, and calculate proportional contributions accordingly. However, further analysis and adaptation would be required to refine this approach into a broader framework applicable to global humanitarian budgets and commitments.

This debate has recently become much more concrete at the European level, and in some cases, it has already been incorporated into legislation. The starting point is the long-established UN framework, which sets a target of allocating 0.7% of GDP as an appropriate commitment for all eligible development assistance (ODA) from donor countries. While this target is not legally enforceable, it remains a binding commitment, even for the German government. It reflects the perspective that donor states bear significant responsibility for poverty and hardship in the Global South. Accordingly, aid is not viewed as charity but as a legitimate entitlement of the affected countries.

Building on this, discussions have recently intensified, particularly within the European Commission and among EU member states, regarding how to define an appropriate share of humanitarian aid within the overall ODA quota. A widely supported proposal suggests that 10% of total ODA should be allocated to humanitarian aid, which equates to 0.07% of GDP in line with the UN’s 0.7% target.

Spain has already enshrined this target in national law, while other countries such as Norway, Sweden, Denmark and even Qatar, have exceeded it. Despite its having the second-highest humanitarian budget in history in 2023, Germany remained well below the 0.07% threshold, allocating only 0.055% of GDP to humanitarian aid. Under the Brussels model, it would therefore be straightforward to calculate an appropriate humanitarian budget for Germany, provided that the country, as it repeatedly claims, remains committed to the 0.7% target and is willing to allocate at least 10% of this amount to humanitarian assistance. This would reflect the growing financial needs of a world where over 300 million people are currently in crisis.

In simple figures, as these narratives often present: an appropriate humanitarian budget for Germany would amount to €3.4 billion. Can we not afford that? The promised tax cuts, primarily benefiting high earners, are projected to cost between nearly €50 billion and well over €100 billion per year.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Spannende Gedankengänge, Danke dafür!

Hier ein paar Reaktionen:

1. Ein zentraler Faktor bei der Frage der angemessenen Finanzierung ist der Bedarf. Eigentlich sollte dieses wahrscheinlich das am schwersten zu gewichtende Element sein, da ja – gerade im humanitären Bereich – Leben davon abhängen. Die nicht-triviale Berechnung einen belastbaren Bedarf zu berechnen macht sich z.B. der Global Fund to fight Aids, Tuberculosis & Malaria alle drei Jahre vor der Wiederauffüllungskonferenz (nennt sich der ‘investment case’).

2. Nicht zu unterschätzen ist auch der Anteil Deutschlands an der Finanzierung der Nothilfe durch die EU. Mit ca. 22% deutschem Anteil am EU-Budget sollte dies natürlich auch einfließen in die Beurteilung des deutschen Beitrags.

3. Was mir am letzten Vorschlag gefällt ist eine automatische Bestrafung von ‘inflated aid’, der üblen Praxis von Geberländern alles mögliche als ODA zu verrechnen. 😉

Wenn die Humanitäre Hilfe am Gross National Happiness (Bruttonationalglück) pro Kopf gemessen würde, lägen wir zur Zeit ganz weit vorne..