| Author: | Maryam Zarnegar Deloffre |

| Date: | 24. October 2023 |

The German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO) is currently drafting a new humanitarian strategy, which will set priorities for the next four years (2024-2027). While humanitarian assistance has become a cornerstone of Germany’s foreign policy and multilateral leadership, the war in Ukraine has ushered in a period of increased defence spending and budget cuts to humanitarian assistance. The strategic planning process thus provides a pivotal moment for Germany to take stock of its role as a major donor to humanitarian assistance and articulate its vision for the future of the global humanitarian system.

By 2016, Germany surpassed the United Kingdom to become the second largest donor of humanitarian assistance by volume after the United States (US). At the World Humanitarian Summit (WHS) in that same year, major humanitarian donors and organizations signed onto the Grand Bargain (GB) an agreement which included an array of commitments to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of humanitarian assistance. In 2021, signatories to the Grand Bargain 2.0 streamlined reform efforts, committing to quality funding and localization as the key enablers of a more efficient and effective humanitarian response. The most recent review in June 2023 confirmed these commitments and highlighted the role of the GB as a catalyst for system transformation.

While Germany is committed to the GB and emerged as a leader in providing quality funding, the draft strategy makes scant reference to localization. By contrast, the US has made localization a centerpiece of its development and humanitarian assistance policy. Based on Germany’s performance on the GB’s two core areas and the US’s recent commitments to localization, I offer four suggestions on how Germany might fully integrate localization into its new strategy.

Quality Funding

The Grand Bargain 2.0 streamlined reforms to two main areas: quality funding and localization. Quality funding mechanisms, such as flexible funding, unearmarked or softly earmarked funds, multi-year grants and pooled funding, shift decision-making about humanitarian programs and projects from bureaucrats in Berlin to implementing partners. Flexible funding mechanisms enable timely responses that allow implementing organizations to make programming decisions in response to evolving needs and to adapt to changing crisis conditions. Multi-year and pooled funding decrease funding uncertainty, which improves the sustainability of programs, encourages longer-term investments, and incentivizes cross-sectoral collaborations across the humanitarian-development nexus.

Germany leads in these reforms, and recipient organizations perceive it as an “honest broker” or “good performer” on quality funding. The GFFO Strategy reaffirms a commitment to efficient, flexible, and anticipatory aid. Annual evaluations of the GB, which draw on data collected from signatories’ self-reports, provide snapshots of Germany’s performance on quality funding.

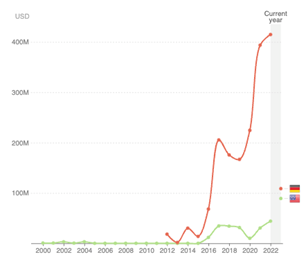

In 2022, Germany reported that 54% of its humanitarian funding was flexible (unearmarked or softly earmarked) up from 24% in 2019, thereby exceeding the GB 30% flexible funding target. Germany reported that 75% of its humanitarian funding was issued as multi-year grants in 2022. Similarly, Germany is consistently a top donor to country-based pooled funds (CBPFs), donating more than ten times as much as the US to CBPFs in 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Contributions to Country Based Pooled Funds by US and Germany from 2000 to 2022

Source: Data compiled by author. Data available cbpf.data.unocha.org.

Localization

Despite a strong rhetorical commitment to localization, official government donors such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and GFFO have not met the GB target of providing 25% of humanitarian funding as directly as possible by 2020. In 2021, only (France, Spain and the Czech Republic) reported meeting or exceeding this target.

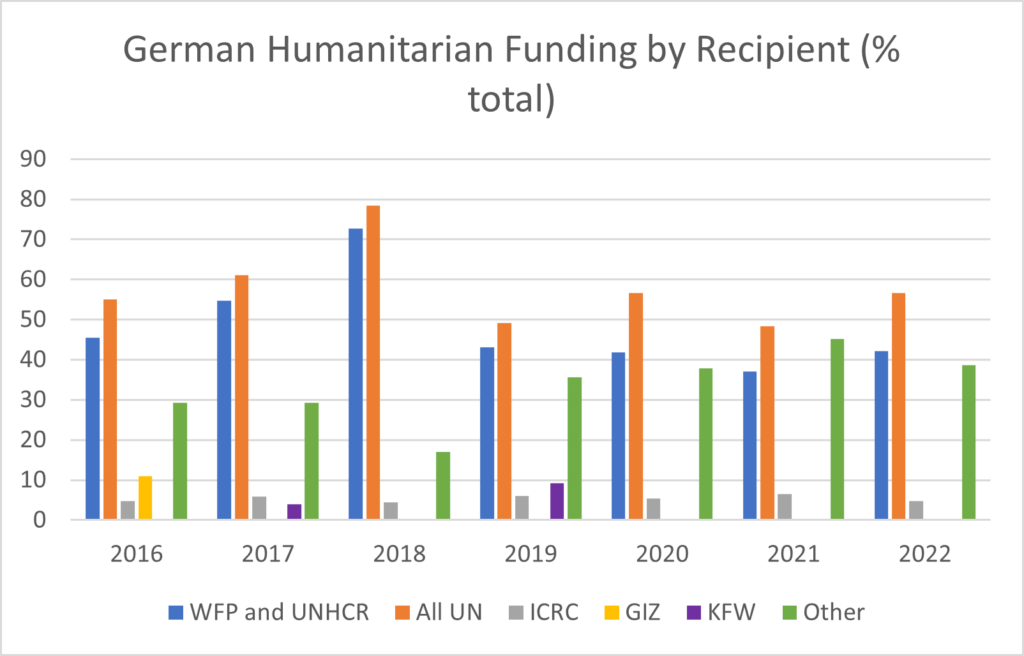

Germany’s long-standing preference for funding large international organizations, which serve as intermediaries between GFFO and local and international implementers, hinders progress towards this goal. In the period since the Grand Bargain (2016-2022), the top two recipients of German humanitarian funding have consistently been the World Food Program (WFP) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). All United Nations (UN) agencies combined received on average 58% of German humanitarian funding.

Figure 2: German humanitarian funding by recipient as share of total funding 2016-2022

Source: Data compiled by author. All UN includes WFP, UNHCR, and other UN agencies.

Data retrieved from UN Financial Tracking Service.

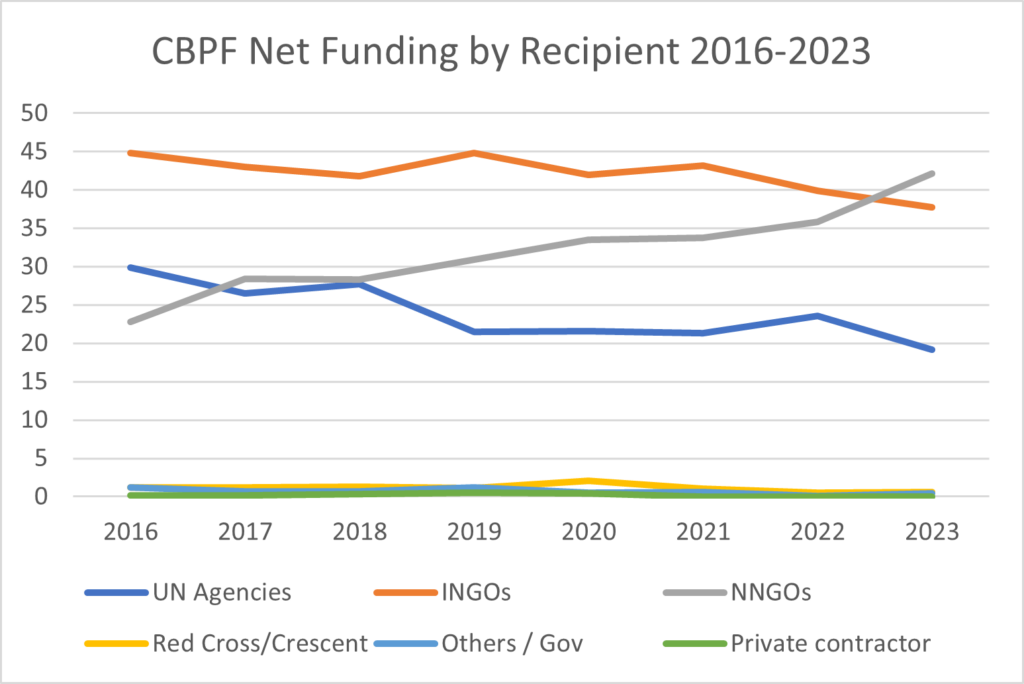

Donating to CBPFs helps Germany meet the quality funding goals and commitments to localization. Top recipients of CBPF direct funding have traditionally been UN agencies and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), which combined received 63.5% of CBPF funding in 2022. At the same time, CBPFs provide the largest source of direct funding for local and national humanitarian organizations of all funding mechanisms. Since 2016, the percentage of funding directed to national NGOs (both as prime and sub-contractors) has increased and surpassed the percentage of funding allocated to INGOs in 2023. German leadership on CBPF reform could help continue this upward trend.

Figure 3: Country-Based Pooled Funds Net Funding by Recipient 2016-2023

Source: Data compiled by author. Data available cbpf.data.unocha.org.

Net funding includes both primary and sub-grant awards.

USAID has made localization the cornerstone of the agency’s work as announced in Administrator Samantha Power’s speech, a “New Vision for Global Development,” in 2021. Since then, USAID has made a dual commitment to a direct local funding target (25% of funding will go directly to local partners by 2025) and to local leadership (50% of USAID programs will be led locally). The second metric is key because it acknowledges that redirecting financial resources is not enough to shift power dynamics. The Locally Led Programs Indicator is focused on relational aspects of USAID-funded activities and measures the extent to which local actors lead priority setting, program design and implementation, as well as evaluations.

USAID has invested significant resources into defining, operationalizing and implementing localization policy and released new guidance such as the Local Capacity Strengthening Policy and WorkWithUSAID.org platform to facilitate partnerships. A recent Progress Report finds in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 direct local funding constituted 10.2% of USAID obligations, the highest level in ten years. This accomplishment is almost entirely due to the health sector’s strong performance; more than half (57%) of all of USAID’s FY 2022 direct local funding was attributable to the US President’s Emergency Relief Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has a long-standing commitment to localization. PEPFAR has made significant strides in increasing the amount of funding directly provided to local partners from 34.9% in 2018 to 55.2% in 2022.

While these advances are commendable, it is equally important to note that USAID oversees both development and humanitarian assistance and between FY 2020-2022 humanitarian assistance recorded the lowest levels of direct local funding by sector. The health sector’s robust results obscure stagnation and decline of direct local funding in other sectors and suggest localizing humanitarian assistance faces unique challenges not encountered in the health sector.

What early lessons can we draw from USAID’s Localization Policy?

1) Localization needs to be supported by increasing staffing levels across missions. According to the USAID evaluation, in FY 2022, missions and overseas units provided the most direct funding to local partners with 18% of obligations directed to local partners. The health sector was a clear leader in this field. In 2018, USAID missions conducted an assessment to determine the staffing levels needed to successfully achieve the PEPFAR localization targets and increased staffing levels to meet these goals. For a donor of its size, the GFFO is notoriously understaffed and staff are centralized in Berlin, which means German missions often do not include humanitarian experts and lack capacity to sustain relationships with local actors. The draft GFFO strategy acknowledges the importance of local presence and the input of German missions in improving humanitarian assistance. The experience of PEPFAR suggests increasing German mission staffing is critical to enhancing the GFFO’s ability to meet localization goals.

2) Localization is not only about redirecting money but also about reconfiguring relational networks to include local partners and strengthen relationships. USAID’s new Locally Led Programs indicator emphasizes building and maintaining relationships. One key to PEPFAR’s success is an intentional strategy to increase communication and strengthen relationships with new and existing local partners. In 2019, PEPFAR organized the first Global Health Local Partner Meeting to provide a venue for cultivating relationships, exchanging information and building relational networks. The GFFO strategy should prioritize these relational dimensions of localization, using USAID’s Locally Led Programs indicator as a model for formulating metrics to track progress on community interactions and participation.

3) Given the small size of Germany’s foreign ministry and consular presence, it might not be realistic to sufficiently grow staff to foster these types of relationships. However, given Germany’s outsized influence as a major donor to pooled funds, the GFFO could examine how missions relate with CBPFs and stipulate reforms to ensure programs are locally led. The GFFO could require that all CBPFs have majority local representation on advisory boards, limit or restrict sub-contracting so most primary contracts go directly to local organizations, revise risk and capacity assessments to ensure local organizations remain competitive for funding and spearhead a Locally Led Programs indicator to evaluate CBPF performance on localization.

4) Increasing flexible and direct funding to local actors will help the GFFO meet its strategic objective to scale up anticipatory humanitarian assistance and link climate, development, and humanitarian programming. Local actors resist the tendency of international programming to distinguish between humanitarian and development assistance and already see the two as related. Locally-led anticipatory action draws on local knowledge and expertise to identify risk, vulnerabilities, and coping capacities.

As the top donors of humanitarian assistance, the US and Germany can play an outsized role in shaping humanitarian policy and reforms. Their policy strengths complement each other. While the US lags in meeting GB commitments for quality funding, Germany excels in this area and as the US is making significant strides on localization, Germany trails. The GFFO strategy should reaffirm German commitments to quality funding and continue leading in this space but also fully integrate localization in these efforts.

Maryam Zarnegar Deloffre, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of International Affairs and Director of the Humanitarian Action Initiative at The George Washington University (Washington, D.C.), a Mercator Fellow at the DFG Research Training Group – Standards of Global Governance (Germany), and an Associate Senior Fellow at Centre for Global Cooperation Research, Universität Duisburg-Essen.

This blog is part of the “Strategy Snacks” with which CHA is accompanying the German Federal Foreign Office’s renewal of its humanitarian strategy.

The “Strategy Snacks” are on the one hand a series of articles on this blog and on the other hand an online event series in the “Out of the box” format at lunchtime.

Related posts

Applying the Objectives and Principles of Humanitarianism to State Diplomacy. A Spanish Case Study.

06.10.2023Three questions for a more feminist humanitarian strategy

27.07.2023Out of the box: Strategy Snacks 2

20.07.2023 12:00 - 13:00