| Autor*in: | Pariwish Abbasi |

| Datum: | 23. August 2024 |

Scroll down to find an audio version of the blog!

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) does not have a strong track record of agreeing on issues related to humanitarian access, including the challenges and the need to advocate for unrestricted access in all current crises, regardless of the political context. This underlines what is at stake when the UNSC publishes a press release, as done in April 2024, sharing its concerns that there has been a ‘shocking increase’ in denial of access to life-saving humanitarian aid.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) defines humanitarian access as a two-pronged concept, comprising humanitarian actors’ ability to reach populations in need and the affected populations’ access to humanitarian assistance. It recognizes that full and unimpeded humanitarian access to emergency areas is essential for the rapid provision of immediate assistance.

This becomes more clear if we look at latest humanitarian trends: Today, nearly 300 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance i.e. 4% of the world’s population. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the total global displacement crossed the 120 million mark in 2024. Importantly, this is the twelfth consecutive annual rise in the global figures for forced displacement. On the other hand, the factors forcing people to leave their homes have also worsened. Violent conflicts, economic instabilities, human rights violations, persecution, disasters, and the impact of climate change remain the leading causes of forced displacement and humanitarian emergencies. While there is an increased need for effective and timely humanitarian assistance, the rise in internal access constraints is becoming a major challenge to the provision of aid.

Defining internal access constraints

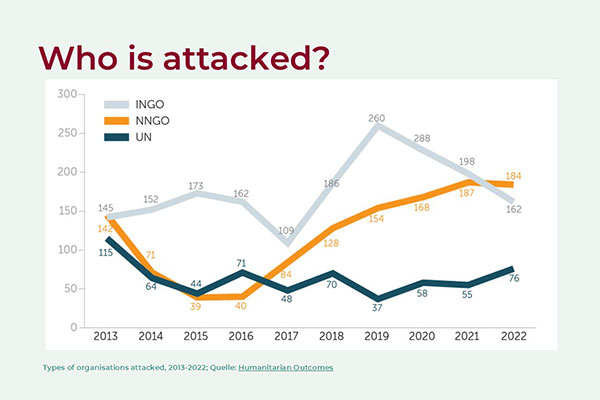

Internal access constraints refer to the deliberate and willful obstruction of humanitarian aid. In humanitarian operations, internal access constraints manifest in a range of ways, with a growing concern centered around increased violence targeting aid workers in protracted conflict zones. Aid workers are becoming a direct target of hostilities and violence perpetrated by armed groups. This includes violent attacks, kidnapping, blockades, arbitrary detention of aid workers, or attacks on the facilities operated by aid agencies such as hospitals. For example, in 2022, 444 humanitarian aid workers were affected by violence in 235 major attacks, resulting in 116 fatalities. Apart from violent attacks, internal access constraints also include state-imposed bureaucratic impediments to limit access to humanitarian aid to the affected population. These bureaucratic obstacles are reflected in the form of delayed or denial of visas to international aid staff, introduction of new administrative processes to the aid agencies, and diversion of aid.

In 2022 alone, the United Nations documented 3,931 verified instances of denial of humanitarian access, mostly by government forces. The highest number of incidents was reported in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Mali.

Understanding the rise in access constraints

It is worth noting that there has been a noticeable uptick in internal access constraints and direct attacks on aid workers after 2000. As Larissa Fast in her book Aid in Danger notes:

‘The humanitarian impulse to provide lifesaving assistance is under fire, literally and figuratively: literally, as aid workers from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe are attacked, injured, kidnapped, and killed, and aid agencies are prevented from accessing vulnerable populations; and figuratively, as the essence of humanitarian action— to provide life-sustaining assistance to those suffering as a result of war or natural disaster— is compromised by those who link such assistance to foreign policy or security goals.’

Despite the challenges related to the absence of reliable data and complex humanitarian operations in conflict areas, the available evidence suggests that both incidents of direct violence against aid workers and deliberate denial of humanitarian assistance have increased. For example, Humanitarian Outcomes reports that between 1997 and 2001, in total, 390 aid workers were affected by major attacks. This number reached 1,341 between 2019 and 2023. Similarly, the Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism of the UN verified almost 23,000 incidents of denial of humanitarian access. Of these, 15,000 were verified in the past five years.

How are access constraints impacting the current humanitarian crisis

This increase in access constraints significantly undermines the effectiveness of humanitarian operations. According to ALNAP’s analysis, access constraints in Ethiopia impeded support to people in Tigray response. In 2021, an estimated 9.4 million people needed humanitarian assistance. Despite the heightened need, heavy politicization, physical and bureaucratic blockades (including on banking, logistics, telecommunications, and travel), the suspension of leading INGOs, and the designation of senior UN staff as persona non grata have imposed major obstacles to the provision of humanitarian aid. Consequently, aid was largely inaccessible to huge parts of Eastern and West Tigray zone. The analysis shows that only 9% of the impacted population reported receiving sufficient support and only 18% said that the support had been timely. The same report highlighted that from 2017 to 2020, the attacks on aid workers rose by 54%.

The Israel-Gaza conflict is another recent example of the steep rise in violence and security risks faced by aid workers. Human Rights Watch reports that since 7 October 2023, 254 aid workers have been killed in Gaza. Importantly, it is worth noting that security incidents significantly accentuate the intensity of challenges and risks aid workers are exposed to; however, they are not the only hurdles to delivering humanitarian aid. Today, aid agencies face a myriad of challenges in ensuring effective and timely humanitarian assistance in countries requiring aid. Sudan is a case in point. Currently, there are 18 million Sudanese facing acute hunger, and the conflict has led to the world’s biggest internal displacement crisis forcing 6.5 million people to leave their homes to seek safety. Yet, since the start of the conflict in Sudan, aid workers have faced a range of restrictions leading to a humanitarian blockade imposed by all warring factions. This includes looting, bureaucratic hurdles, weaponization of aid, aid diversion, and temporary suspensions of aid operations. Besides Gaza and Sudan, numerous other countries are grappling with internal aid restrictions based on their specific contexts, including Afghanistan, Yemen, and Syria.

Navigating Access Constraints

Finding a simple solution for the surge in constraints on aid workers‘ access is not straightforward, and the debate on the matter has been ongoing for years. However, the alarming twofold trend of rising needs and rapidly rising access constraints highlights that the issue needs to be prioritized and action to go beyond lip service, in particular by leading humanitarian donors. This alarming rise in internal constraints calls for serious attention to the issue. For a start systematic analysis of the causes and the impact of internal access constraints on humanitarian aid is critical. Considering the key role recipient states play in providing access, humanitarian diplomacy is key and needs to be better resourced and better backed in foreign policy approaches. Further actions that can potentially improve current limitations include strengthening relations with recipient countries but also local leaders, which is becoming ever more relevant due to the rise of fragile humanitarian contexts. Providing security training to national project staff is key, as local staff is in the focus of the violent attacks’ rise (see graphic). Integrating access planning at the project inception stage, incorporating conflict-sensitive project management, and systematically documenting best practices for negotiating access in conflict zones are further essential tools. The rapidly evolving humanitarian landscape requires deliberate planning to restore access and provide aid to the most vulnerable.

We have known for many years what needs to be done. It is time to show rather than tell, as the outlined trends reveal a new dimension: these challenges need to be tackled more seriously and comprehensively than in the past. We also know that political actors have the potential to play a decisive role in managing access constraints, particularly by pressuring recipient states to ease barriers to aid. For example, on August 15, 2024, Sudan’s Sovereign Council announced that it will temporarily reopen the Adre crossing to allow humanitarian aid into Sudan. This decision was made in response to intense pressure from humanitarian agencies, with the US and UK governments among those lobbying for the reopening of the Adre crossing. This highlights that political actors can play a leading role in ensuring the success of humanitarian diplomacy. However, as noted earlier, achieving consensus from the UNSC on political issues remains difficult. This underscores the need to ensure that humanitarian imperatives are upheld, and that assistance reaches those in need, regardless of the political context. As Jean-Martin Bauer of the WFP said, „Conflicts are complicated, but the moral imperative to ensure civilians are fed should be quite straightforward.“

Pariwish Abbasi has worked with notable international not-for-profit organisations and is a trained Humanitarian Practitioner.

Listen to the blog (created with Murf AI):

Relevante Beiträge

Abkehr vom Humanitarismus ?

24.05.2024Wo humanitäre Diplomatie möglich und höchst notwendig ist

10.08.2023Humanitäre Hilfe als Kampfmittel?

12.07.2022